John A. Lent

I arrived in Penang the Summer of 1972, with my then wife and four toddlers (the oldest seven, the youngest three), a few cheap, flimsy trunks of our belongings that split somewhere between Iowa and Hong Kong, and much anticipation about my new lifestyle and position and excitement about being back in Asia. (I had shipped the family pet dog, a female mongrel named Socrates, weeks before, in care of Dean Robert Van Niel, much to his surprise and chagrin.)

After settling in at 10 Hargreaves Road, I began my orientation to Malaysian academic life. I think I was bewildered by the highly-structured nature of Universiti Sains Malaysia (then in its third year and only recently renamed after being Universiti Pulau Pinang), bowled over by the generous benefits package that was given us, and a bit embarrassed by the tremendous degree of respect students showed.

Although I use the term “highly-structured” now, in 1972-74 I thought it was too bureaucratic, not appreciating then (or now) the need for a 16-page contract and long minutes of every transaction in both Bahasa Malaysia and English. On one memo, I wrote: “In a place short of paper, these minutes come out in English and Bahasa and the administrative assistant sends a cover letter saying we’re getting them.”

I found other things perplexing or counter to my style of life, such as the formalness of the classroom and the great amount of suspicion everywhere. Students rose when I entered the classroom (a practice which I and other expatriate lecturers soon abandoned) and, in the beginning, they were hesitant or shy to speak in the classroom. It was not very long before I broke down some of the formality, even having the class meet outdoors on an occasion or two. Administering and taking final examinations was a very serious matter, with first aid kits in the room for students who might faint or otherwise be sickened by the ordeal, and a couple or more of us faculty members serving as invigilators. I recall serving as invigilator for an Introduction to Visual Arts exam where the lecturer showed slides of art works in a semi-darkened room and we roamed about with flashlights in hand.

Early on, I was told of the four sensitive issues not to be broached on any occasion and warned that some students doubled as government spies. Certain books were off limits and in the university library, a banned books room was maintained that we had access to only with special permission. On its shelves were politically-sensitive books (including Mahathir’s The Malay Dilemma) and those considered obscene or vulgar. One must remember this was only three years after the May 13 riots. Nevertheless, I never felt hampered or censored and engaged in critical discourses with colleagues and students.

I recall the friendly and aesthetically-pleasing atmosphere of the Minden campus. With a population of about 1,100, and each of the two upper-level communication batches (second- and third-year) limited to about 20—25 majors, there was ample time to interact with students, despite my initial difficulties addressing them because of the multiplicity of cultures and languages. (Poor Shirley Tan and Molly Mathews whom I called on often in the beginning because of their Anglicized, and therefore, more familiar names.) At Universiti Sains Malaysia, I felt I was part of a large family, whose members were cordial and respectful. The Vice Chancellor Hamzah Sendut was very accessible, holding little get-togethers with each of us newcomers in the “Water Tower” and knowing all of us by name. One conversation I recall having with him dealt with my not wanting an automobile. USM at the time offered interest-free car loans to faculty, and Hamzah could not understand why I would ride the bus instead. (I told him because I wanted to be with the public, to get a feel for Malaysian life.)

The faculty was like a miniature United Nations, with lecturers coming from many countries and from all over Malaysia. The coffee breaks at the little outdoor shop at the bottom of the hill were stimulating affairs, mixed with serious academic discussions, Malaysian society news, and local gossip and anecdotes. Humanities and Social Sciences faculty intermingled on these occasions and at social functions in the evenings or on weekends. We enjoyed one another’s companionship. Many of the faculty were or were about to become well-known globally for their research and writings – Shahnon Ahmad, Lim Teck Ghee, Harry Aveling, Peter Bowler, Tone Brulin, Elmer Ordonez, Christophe Harbsmeier, and others.

The campus was breathtaking in its beauty, surrounded by mountains and ocean, with sparse buildings in natural settings. Even then, it was a university in a garden although that phrase was not yet used. The drive from the small airport in Bayan Lepas was through coconut groves (the multinational factories which eventually destroyed that beauty were just arriving about that time) and George Town itself was quaint, exciting, and colorful, with its small buildings, plentiful street vendors dishing out unique and delicious cuisine, rambling E&O Hotel, The Esplanade, and encased by Penang Hill and the yet-unspoiled beaches of Batu Ferringhi.

When I came to USM, my duties as coordinator of the Communication Program, the first of its kind at the university-level in Malaysia, were to redesign the curriculum and teach half of the courses with Vincent Lowe, an instructor who had just received his MA in the United States. The Communication Program was started in 1971, with rather non-distinguishable courses, namely, Mass Communication, Journalism, Audio Visual Media, and Writing for Mass Media; all offered at levels “I” for second-year students and “II” for third-year students. Another course, Mass Media in Education and Development, was on the schedule when I began to teach. These were the courses the two of us shared in 1972. Prior to my arrival, the courses were taught by visiting lecturers from the media based in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore who flew in every week. Some were distinguished media practitioners working with the Asian Mass Communication and Information Centre (AMIC), UNESCO, National Broadcast Training Centre (NBTC), South East Asia Press Centre, CEPTA TV, etc. During my stint at USM, we maintained close liaison with these media leaders and others.

To redesign the communication curriculum was a formidable challenge. Whenever I told Dean Van Niel I did not feel I knew enough about Malaysia and its mass media to carry out the task adequately and appropriately, his reply was always “Read the Rukunegara.” But the National Ideology was vaguely stated and not of much specific help. Eventually, we did change the program, establishing an Introduction to Mass Communication course for first-year students, five others for the second-year (Communication Theory, Media and Society, Mass Media Production and Direction, Mass Media Reporting and Writing, and Communication and Culture), and six for third-year students (Communication Research and Methods, Mass Media [Advanced Production and Direction], Mass Media [Advanced Reporting], Comparative Media Systems, Development Communication, and International Communication). Second-year students were required to attend a one-week familiarization-with-media program in Kuala Lumpur, and during their long holiday, serve a six-week internship with Kuala Lumpur based media, four weeks of which were at NBTC. During the five-day field trips, when they were housed at Wisma Belia at $3 per night, students became acquainted first-hand with Radio Malaysia, Television Malaysia, Malay Mail, Bernama news service, Grants Advertising, Shell Oil public relations, NBTC, Department of Information, Filem Negara, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather, New Straits Times, and Utusan Melayu. The on-campus production courses were set for an entire morning once a week to allow students to follow through all stages of media work in sequence (from reporting to writing to editing or broadcasting).

The new curriculum was one to be proud of, even surpassing many longer-established undergraduate programs in the United States in its scope, rigor, and depth. The courses were oriented toward both research/theory and practice and were interdisciplinary in nature. They revolved around communication skills, humanistic approaches to communication, and development and international communication. The latter were especially appropriate at the time with Asian governments’ and NGOs’ emphasis on using communication for national development purposes. Development communication was the buzzword of the day.

Students were expected to do actual reporting and writing in simulated assignments on campus and real-world situations during their internships. We even had press cards printed for them. Third-year students were required to carry out original research, using primary resources and techniques such as historical method, content analysis, interviews, or audience and other surveys. The papers they wrote for my courses dealt with a variety of topics, and I think it necessary to mention representative ones here for there is no doubt, these were the pioneering studies of Malaysia’s mass communication. Examples were: Shirley Tan Lee Nah’s history of Penang journalism, 1911—1945; Primalani Muthucumaru’s Straits Echo history; Cheah Kim Lean and Rodziah Ahmad Tajuddin’s treatment of Malaya’s underground press, 1942—1960; Molly Mathews’ history of Malaysian broadcasting; Mohd. Naim Ismail’s work on Suara Malaysia; Parameswari’s analysis of government press releases used by five Malaysian dailies; Ismail bin Mamat’s content analysis of Straits Times and Utusan Melayu and Tuan Kamaruzaman’s similar study of Utusan Malaysia and Straits Echo; Lee Wai Keong and Venugopal’s “Research Projects on Women’s Magazines”; Lee Kim Har’s history of Kwong Wah Yit Poh, 1910—1945; Ng Seng Kang’s work on Chinese culture, language, and press; Cheok Chye Sin’s content analysis of two Chinese newspapers; Rajan Moses and C. Mathew George’s comparison of The Star and Sing Pin Jit Poh; Othman bin Haji A. Rashid’s study of Malaysian mass media during the Japanese occupation; Ainon Haji Kuntom’s history of Malay newspapers; Abdullah bin Mahmood’s content analysis of Utusan Malaysia and Utusan Melayu; Aziz Muhammed and Zainie Rahmat’s study of the Ministry of Information’s use of folk media to disseminate government policies; Bachan Kuar Gill’s survey of the Punjabi press in Malaysia; G. Parimala Devi and N. Nirmala Devi’s project on the availability, penetration, and utilization of media in a Tamil community, and Penelope Tan’s work on Malaysian films and the censor. I think a few were published and I used, with proper acknowledgement, some of the students’ findings in a series of articles and a monograph I wrote on Malaysian mass communication. I had that much confidence in the way the research was conducted.

Communication studies quickly became very popular at USM. By Summer 1973, the Introduction to Mass Communication course enrollment was 143, leading all seven introduction courses in the School of Humanities. This figure takes on added importance considering total on-campus enrollment in the school was 364. We had 28 second-year majors at that time, second only to history’s 37, and 18 third-year students, third of the school’s five majors.

As the communication program was being revamped in late 1972 and early 1973, we were promised additional faculty and better facilities and equipment. But the added faculty did not arrive in time for the short term in 1973, and Vincent and I found ourselves teaching something like 16 courses between us. The next term, we were joined by Don Guimary, Marvin Bowman, John Machado, and two graduates from the school’s first batch, Mansor bin Ahmad and Kuah Guan Oo. Mansor stayed a short time before joining another of the 1973 graduates, Hamima Dona Mustafa, as ASTS fellows pursuing PhDs in the U.S. We also had hired others, including Crispin Maslog and Shelton Gunaratne. Shelton arrived in 1974, shortly after my departure. However, Cris was denied approval by Marcos’ officials to relocate to USM as the newspaper he published had offended Marcos with its coverage of imposition of martial law. The communication faculty quickly became one of the largest in the school.

Upon my arrival in 1972, we had little in the way of facilities and equipment. Our main teaching areas were two small buildings – identified as “108L” and “109L.” At my request, Dean Van Niel requisitioned the bursar on September 13, 1972, for funds to convert 109L into a “Newsroom.” I had asked that a large curved desk be built as a copy desk, as well as a newspaper rack. I also asked for an opaque projector and screen, a telephone, and chairs and table space for 25 people. Students were to learn photography in the Media Centre under Bob Crock. By March 1973, a request was made to “move out of 108L and 109L into a more permanent, less crowded, less noisy building.” Gradually, equipment was added so that a June 25, 1973 capital equipment/recurrent costs inventory showed we had 15 Olivetti typewriters (sometimes down to as few as 11 when some were loaned out), 17 typing chairs and tables, three long-tables, one bench, one bulletin board, 20 rulers, two staplers, one paper cutter, two tape-dispensers, two pencil-sharpeners, two scissors, and supplies. Additionally, the Newsroom had subscriptions to Straits Times, Star, Echo, and Utusan Malaysia. In 1973—74, the situation improved. The copy desk, which I was very proud of, was built; blueprints were drawn up to convert 108L to a makeshift broadcast studio using “intermediate technology” (at one point, the “intermediateness” was such that Vincent and I considered building a small studio using egg cartoons for sound proofing), and Bernama teleprinter service was subscribed to. Marvin Bowman added more broadcasting equipment after he became a faculty member.

Initially, library holdings in mass communication were meager, consisting of books donated by the United States Information Service, if I recall correctly. But, the situation improved as we were asked to make lists of books that the library would purchase. Subscriptions to top mass communication journals and periodicals also increased.

The last term I was at USM, the curriculum was again changed, with one first-year course, four second-year, and 13 third-year. Third-year offerings now included Broadcast Management, Print Management, Introduction to Public Relations, Advertising, Film for Broadcasting, Research Methods, Development Communication, and a graduation exercise (a 10,000-word or less project, bound, and deposited in the university library). We also had started an MA degree program, one of the first in Humanities; among the first students were Hamima Dona Mustafa and Mansor Ahmad (both cancelled when they received ASTS fellowships), Kuah Guan Oo, and John Machado. I think I was to be advisor to all four. I remember that John finished with a thesis on advertising in Malaysia.

The Communication Program was always a beehive of activity, with regular visits of media practitioner friends such as Jack Glattbach, Howard Coats, R. Balakrishnan, and Alan Hancock, and delegations of visiting practitioners and academicians whose Kuala Lumpur hosts thought would enjoy a few days in Penang. On separate occasions, we hosted a group of Indonesian teachers and broadcasters, a University of Hawaii study tour, and individuals such as John Wilhelm, Alex Edelstein, Josie Patron, Edward Wakins, Chan Yen Fooi, Huber Ellingsworth, Flor Rosario, and many more.

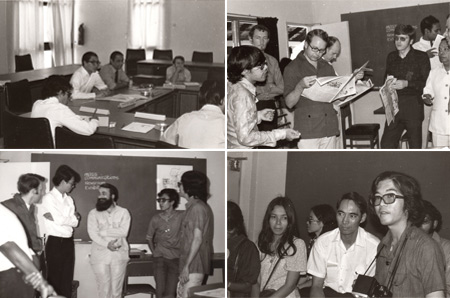

Because we wanted to meet the needs of Malaysian mass media, practitioners were invited on campus to give us guidance. In late 1973, we held a two-day evaluation of the program attended by 29 representatives of commercial, industrial, and government organizations. Among those from the media were Samad Ismail (Straits Times), Mohamed Sopiee (Bernama), Dol Ramli (Department of Broadcasting, Ministry of Information), John Nettleton (Filem Negara), and Ahmad Nordin bin Haji Mohd. Zain (Department of Information, Ministry of Information). That there was still some hesitancy to hire university-trained journalists was expressed by one press representative who said cadet journalists who start from “scratch” with lower academic qualifications sometimes make better journalists than degree holders because they are more humble and less costly.

“Program evaluation meeting.” “Program evaluation meeting.”

There was certainly much to do as coordinator of a new program in a recently-established university. It was not unusual to spend 16 hours in the classroom weekly (take note my junior colleagues who complain about 9-hour teaching loads) and many more than that grading writing assignments and research papers. Additionally, there were the many meetings to attend, reports to write, MA students to supervise, student newspaper Grasiswa to advise, my own research to do, and arrangements to make for student internships, purchase of equipment, hosting of campus visitors, etc. There were also the off-campus centers in Kuala Lumpur, Seremban, Melaka, and Kota Bharu that had to be visited and lectured to at least once yearly. Every day’s work began early and ended late and we were on campus at least half day on Saturdays. But, despite this workload, the whole experience was exciting and productive, and without a doubt, those 19 or 20 months were among the most pleasurable of my 51-year teaching career.

Responsible for most of my enjoyment were some of the most intelligent and open-to-learning students I’ve had the pleasure to work with. The success that many of them have since earned attests to their diligence and brilliance.

I left Penang January 12, 1974. My last four days at USM were as I described them at the time, “one of the most emotion filled periods of my life.” Let me quote some from a diary I wrote:

“[On January 9] I came into my final International Communication course at 8 this night, on the chalkboard was a sketch of me done by Chee Wing – with words in Malay, ‘Bon Voyage and we’ll meet again.’ Signed by all students. After my name they put the word in Malay for ‘godfather.’” After class that night, the students wanted to have a party for me and “mobilized 7 motorbikes and 2 cars and 16 of them took me to the Esplanade for a big feed” which lasted til 2 a.m.

Over the course of the next three days, delegations of students came to my office to chat and express their feelings. On one occasion, the communication students had a slide-show in my honor, showing pictures of the campus and a farewell party they had in my honor; at another time, Social Science students had a tea in my office complete with a cake decorated with “To Dr. Lent with Love.”

“12 January 1974: A farewell group picture with colleagues and students at the Penang airport.” “12 January 1974: A farewell group picture with colleagues and students at the Penang airport.”

The day I left was unbelievably sad. About 80 students and faculty showed up at the airport to see me off and to present me other presents – a photo album, a key chain, and even a stapler! I wrote in my diary: “As I am going to plane, I am openly crying and sobbing. Students saying ‘Goodbye Dr. Lent, glad to have known you,’ etc. Waving from balcony and singing ‘He’s a jolly good fellow’…. The most emotional day of my life, probably.”

Nearly 40 years later, it is still one of the most emotion-packed periods of my life and still brings a tear to my eyes, testifying to the strong bond that these Malaysian communication studies pioneers and I had formed.

John A. Lent taught at the college/university level for 51 years, beginning in 1960, including stints as the organizer of the first journalism courses at De La Salle College in Manila; founder and coordinator of Universiti Sains Malaysia communications program; Rogers Distinguished Chair at University of Western Ontario; visiting professor at Shanghai University, Communication University of China, Jilin College of the Arts Animation School, and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Prof. Lent pioneered in the study of mass communication and popular culture in Asia (since 1964) and Caribbean (since 1968), comic art and animation, and development communication. He has authored or edited 77 books and monographs and hundreds or articles and chapters in books. Additionally, he publishes and edits International Journal of Comic Art (which he founded) and Asian Cinema (1994-2012), chairs Asian Popular Culture (PCA), Asian Cinema Studies Society (1994-2012), Comic Art Working Group (IAMCR) since 1984, Asian-Pacific Animation and Comics Association, and Asian Research Center for Animation and Comics Art (all of which he founded). He also founded the Malaysia/Singapore/Brunei Studies Group of Association for Asian Studies in 1976 and its quarterly periodical, Berita, which he edited for 26 years.

Prof. Lent has lectured or presented papers in 62 countries.

Email: jlent@temple.edu

|